Women's health depends on the guarantee of their sexual and reproductive rights. Historically, the legislation around these rights has been and remains a major issue for the emancipation of women around the world.

In France, contraception and voluntary termination of pregnancy (abortion) are legal and theoretically available to any woman wishing to benefit from them, as part of a public health policy aimed at equal access to primary care. Statistically, one in three (1) women will need to have an abortion during her life.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, the French legislator has adapted the legal framework authorizing general practitioners to perform abortions in town offices1, in family planning centers and health centers2. The law thus adapts to the practices and needs of patients, approaching abortion as an act of first necessity and a real public health issue.

Women’ migration is becoming an important component of international migration. The UN report on international migration (2) shows that nearly half of the 272 million international migrants worldwide in 2019, were women.

In France, percentage of female among all migrants’ range between 50 to 52%

(2) There is a great variety of migrant women with different socio-economic status, they can be documented or undocumented and might have different linguistic capabilities and ethnic backgrounds. Nevertheless, studies show that female migrants have similar characteristics since they face intersecting vulnerabilities of gender, ethnicity and social class (3) and might experience violence (4).

Unsuccessful access to safe abortion services is a reality even in countries with very advanced policies (5). Migrant women seem to be more vulnerable to unwanted pregnancies (6) and often face more challenges to access sexual and reproductive health services than the local population (7).

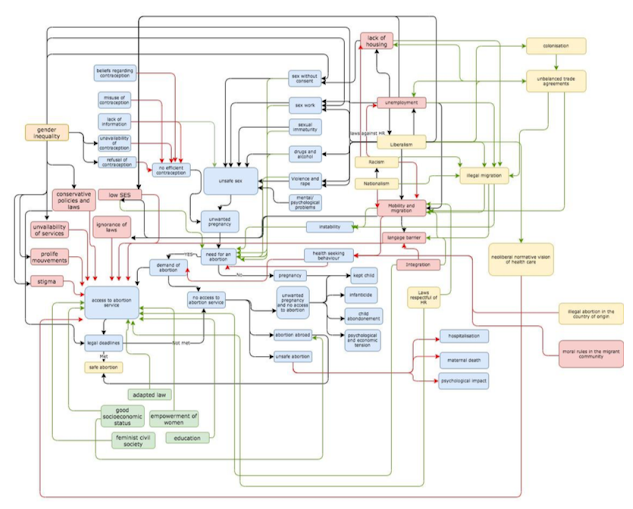

This article will focus on social determinants to access safe abortion services in low-skilled and low-wage economic female migrants in France through the Abortion system Map. The main objective of this article is to explore the various social determinants of vulnerabilities that may hinder access to the medical abortion course for this population through a critical analysis of the Abortion system map.

Access to abortion system map:

Unintended Pregnancy is a consequence of interplay between determinants related to individual physiology, sexual behavior and contraception. This individual behavior is set in a framework designed by many interconnected factors.

Access to abortion system map is made up of a large number of determinants.

Variables are represented by boxes: social determinant that are barriers are in red and the enablers are in green.

Interactions are represented by arrows: positive feedback is represented in green and negative feedback is represented in red.

The central loop is the physiological loop and it is represented in blue. This loop tackles the SDH3 at the individual and familial level.

The green enablers and red barriers tackle the SDH at the social level. The yellow and white boxes tackle more distal Macroenvironmental SDH. Critical analysis of the access to abortion system map:

The access to abortion system map improves the insight into the underlying structure of this complex health issue but doesn’t show the level of influence between variables. Indeed, migration seems to intensify barriers.

This system map is also made up of a number of determinants, some are measurable while others are difficult to quantify.

At the individual level, it presents the contraception as a women’s issue: in this framework men aren’t involved neither in contraception, unsafe sex nor in unwanted pregnancy. The risk is to exclude men from sexual and reproductive health programs’ planning.

Literature shows that vulnerable migrant women in European countries, have less individual agency (8): tend to have limited use and access to contraception and abortion and might look for unsafe abortion procedures (9,10). They seem to be relying on less effective methods of contraception so unintended pregnancy and abortion are common. (11)

One can also argue that these patients might also have a different health services seeking behaviors since in several countries of origin, abortion is prohibited by law and sometimes, depending on the contexts, there may be traumatic or post

-traumatic conditions (12).

But a study shows that this Sick-role behavior (13) is more influenced by cultural issues than the legal interdiction of this practice (14).

At the social level, Mobility and migration are crucial determinants that can affect vulnerability to unintended pregnancies flowing similar mechanisms as in HIV transmission (15). Some authors also link this to the change of the socioeconomic and cultural contexts before and after migration (16).

Social Determinants of Health

At the global level, this framework takes into consideration the politicized dimension of sexual health as a form of biopower: through the strict definition of the duration of pregnancy that gives the right to abort, the government controls women's bodies. During COVID crisis, restrictive measures and reduced freedom of movement obstructed access to safe abortion. Many patients missed the legal deadline. Lately, a law proposition has been discussed and validated to extend the legal period from 12 to 14 weeks for having recourse to abortion (16).

Policies implications and recommendations:

Safe abortion is a universal complex health issue that needs a multidimensional response. The priority is to focus on proximal barriers in order to have quick improvements.

The social and economic forces that constrain the agency of vulnerable migrant women need to be addressed first through actions aiming proximal SDH like language barriers, dissemination of information through channels adapted to each population, better employment conditions. Then distal SDH need to be addressed through flexible policies as in the Netherlands, where abortions are performed until approximately 24 weeks of pregnancy.

In conclusion, a feminist approach is needed within mobility studies in order to produce data about the “creation of new geographies of belonging and exclusion” (17) which has a great impact on health in migrant women.

“Never forget that a crisis will suffice for women’s rights to be threatened. These rights are never granted. You need to remain careful, your entire life”. (Simone Veil)

Notes:

1 law n ° 2001-588 of July 4, 2001

2 law n ° 2007 -1786 of December 19, 2007

References:

1. Mazuy, M., Toulemon, L. and Baril, É., 2015. Un recours moindre à l’IVG, mais

plus souvent répété. Population & Sociétés, N° 518(1), p.1.

2. United Nations department of economic and social affairs Population Division. 2019. International migrant stock 2019. [online] Available at:

<https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates 2/estimates19.asp.> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

3. Llacer, A., Zunzunegui, M., del Amo, J., Mazarrasa, L. and Bolumar, F., 2007. The contribution of a gender perspective to the understanding of migrants' health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, [online] 61(Supplement 2), pp.ii4-ii10. Available at:<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2465778/> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

4. ReliefWeb. 2021. UNFPA State of World Population 2006: A Passage to Hope - Women and International Migration - World. [online] Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/report/world/unfpa-state-world-population-2006-passage- hope-women-and-international-migration> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

5. Klein, J. and von dem Knesebeck, O., 2018. Inequalities in health care utilization among migrants and non-migrants in Germany: a systematic review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1).

6. Rokicki, S., Montana, L. and Fink, G., 2021. Impact of Migration on Fertility and Abortion: Evidence from the Household and Welfare Study of Accra. [online] Available at:<https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/slawarokicki/files/rokicki_migrationfertility_wp_0.pdf> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

7. Foundation, T., 2021. What the lack of access to safe abortion means for migrant women. [online] news.trust.org. Available at:

<https://news.trust.org/item/20190927142655-3gkuh/> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

8. Clark University, and International Center for Research on Women, 2021. the AIDS Response: Building AIDS Resilient Communities, International Development, Community and Environment. Aids2031. [online] Washington: Social Drivers Working Group (2010). Available at:

<https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rj a&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwi6_qGljYnxAhWDyIUKHTDPBOEQFjABegQIBBAD&url

=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.comminit.com%2Fla%2Fcontent%2Frevolutionizing- aids-response-building-aids-resilient-communities-aids-2031- internationa&usg=AOvVaw0hDDRQlK5bPN97wtODmc4E> [Accessed 1 June 2021].

9. PICUM. 2016. The Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights of Undocumented Migrants: Narrowing the Gap between their Rights and the Reality in the EU.. [online] Available at: <http://picum.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Sexual-and- Reproductive-Health-Rights_EN.pdf> [Accessed 4 June 2021].

10. Emtell Iwarsson K, Larsson E, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Essén B, Klingberg-Allvin

M. Contraceptive use among migrant, second-generation migrant and non- migrant women seeking abortion care: a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted in Sweden. 2020.

11. Zong Z, Sun X, Mao J, Shu X, Hearst N. Contraception and abortion among migrant women in Changzhou, China. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2020;26(1):36-41.

12. Vilain A. Les femmes ayant recours à l'IVG : diversité des profils des femmes et des modalités de prise en charge. Revue française des affaires sociales. 2011;1(1):116.

13. 4. Kasl S, Cobb S. Health Behavior, Illness Behavior, and Sick-Role Behavior. Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. 1966;12(4):531-541.

14. Pilecco F, Guillaume A, Ravalihasy A, Desgrées du Loû A. Induced Abortion and Migration to Metropolitan Paris by Sub-Saharan African Women: The Role of Intendedness of Pregnancy. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2020;22(4):682-690.

15. O'Laughlin B. Trapped in the prison of the proximate: structural HIV/AIDS prevention in southern Africa. Review of African Political Economy. 2015;42(145):342-361.

16. Quatre questions sur la proposition de loi visant à renforcer le droit à l'IVG en France [Internet]. Les Echos. 2021 [cited 6 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.lesechos.fr/politique-societe/societe/quatre-questions-sur-la- proposition-de-loi-visant-a-renforcer-le-droit-a-livg-en-france-1254110

17. . Side K. A geopolitics of migrant women, mobility and abortion access in the Republic of Ireland [Internet]. Academia.edu. 2016 [cited 6 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/30578728/A_Geopolitics_of_Migrant_Women_Mobilit y_and_Abortion_Access_in_the_Republic_of_Ireland

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire