Et pourtant elle tourne;

13 avril, 2024

Le capitalisme est-il mauvais pour la santé ?

12 mars, 2024

Female Genital Mutilations: Were women liberated by globalization?

The 6th of February is the International day of Zero Tolerance for the Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)[1].

Despite the actual proliferation of actions and initiatives to fight FGM and the global political importance it has, the classification of FGM as a human right violation and a global health problem is recent.

The consideration of FGM has been largely driven by globalization: FGM is one of the topics where the interests of different stakeholders, their ideologies and interactions[2] led to different health policymaking processes during time.

We will trace in this article how globalization provoked a shift in the international policy system through the modification of the normative basis of the WHO governance at many times in human history [3] and how the internationalization[4] of the fight against FGM led to actual policies and even the design and implementation of health programs aiming the “Sexual Reparation” for Women with FGM [5], implementing a globalized culture around women sexuality.

The 19th century was the era of colonial expansion. During this period, the spread of the European empires ignited the first waves of globalization[4]: the world witnessed the proliferation of Western norms in the conquered territories.

During the first wave of globalization, the missionaries and colonial administrators had pointed out the practice of FGM, which they described as barbaric. The colonizing authorities tried then to remedy these practices through education, but these initiatives triggered an “indigenous resistance”[6].

The political stakes pushed the colonizing countries to adopt a neutral view. This positioning was then supported by ethnological studies performed between the 19th and the 20th century qualifying FGM as “traditional cultural practice”[7], considered as rites of initiation or passage[8], with a consensual discourse on the inferiority or primitiveness of the savages who populated the colonized territories [9].

The question of FGM was dealt with for the first time, within the United Nations, in 1952[10]. But the WHO aligned with wealthy country interests[11] and declined any initiative aiming to act upon this issue[10].

In short, during colonization and despite the movement of populations and the transfer of norms due to the two first waves of globalization, economic interests of the colonizers prevailed and FGM failed to be considered as a health problem by the WHO[13]: the public health normative goals aiming a good population health, were undermined by the economic interests of the colonizers[12].

Yet, FGM started to be part of the WHO agenda during the 70s. This radical change in WHO positioning was due to several facts:

-At the end of the 2nd World War, several legal documents in favor of human rights were born and two social groups acquired a new importance: women and children[5].

-From the end of the 1950s, the process of decolonization launched the debate on the recognition of the autonomy of populations as well as the recognition of fundamental human rights, which changed the relationship between North and South. The emergence of decolonized African nations had a great impact[2], since new countries started taking part in the discussions as UN member-states which gave space to different voices to be heard, like the Sudanese Women's Union (SWU) which were strongly positioned against FGM [13].

- At the same time, modern migratory flows starting in the 1960s had a significant impact on the representations and practices of FGM in host countries. FGM became an imported phenomenon in Western countries. Western governments feared homogenization given the spread of these foreign cultures and questions of citizenship, nationalism, ethnicity, difference[4] but also power and racism were lit : the former colonized migrating to the former colonizing countries cause these distant practices to become close and call into question the norms of migrant populations[10]. Thus, Western countries felt the urge to restore a normative infrastructure[4] through developing policies and pushing WHO to adopt a more proactive position.

-The interventions of white non-governmental organizations and Western activists were crucial: The Western feminist fight adopted the struggle against the FGM thus propelling the issue internationally and the movement of sexual liberation started using this topic as Trojan horse in advocating for more rights.

Under these conditions, WHO finally decided to consider FGM as a public health problem and to start taking actions in 1976 during the meeting in Cairo [10].

Between 1990 and 1995, several conferences dealt with FGM: International community started by qualifying it as a form of violence during the Beijing conference and ended up defining it as a Crime [5].

Subsequently, there have been a plethora of International and National Legal Frameworks and countries were urged to implement policies criminalizing FGM[14] encouraged by The Global Forum on Law, Justice and Development initiated by the World Bank and accounting numerous and various partners[15].

Now, FGM is recognized as a human right violation and as a public health problem.

Many initiatives to fight FGM have been implemented by transnational civil society in countries with high rate of gender-based violence and FGM, which also became a subject for health policy aimed at repairing feminine sexuality since 2000.

Nowadays, France has positioned itself as the leader country in Good Health Governance[3] when it comes to FGM. In France, women victims of FGM have the right to seek asylums[16]. France is also the only country that recognizes the right to medical healthcare for victims of FGM: the French mixed Bismarckian and Beveridgian social security system[17] extends coverage to non-contributing populations and started including migrant women victims of FGM since 2004 [10].

This specific sexual reparation program proposes interventions aiming the reinstitution of “normal female sexuality” [5].

It seems to be an attempt to regulate feminine sexuality through promoting universal norms about female sexual normality which happens to be Western. Indeed, the notion of normality or “abnormality” [5] seems to be linked to the pattern of migration with a dominant model portrayed in the media which has been reported to reinforce the social stigma [5].

Globalization seems to be, as Denis Altman says, liberatory and oppressive at the same time [18] when it comes to women sexuality.

References:

[1] EQUINET EUROPE. 2019. 6 FEBRUARY: INTERNATIONAL DAY OF ZERO TOLERANCE FOR FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION (FGM). [online] Available at: <https://equineteurope.org/6-february-international-day-of-zero-tolerance-for-female-genital-mutilation-fgm/> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[2] Brown, T., Cueto, M. and Fee, E., 2006. The World Health Organization and the Transition From “International” to “Global” Public Health. American Journal of Public Health, 96(1), pp.62-72.

[3] Lee, K., Kamradt-Scott, A. The multiple meanings of global health governance: a call for conceptual clarity. Global Health 10, 28 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-10-28

[4] MCGREW, A., (2014) ‘Globalization and global politics in The Globalization of World Politics’ London: Oxford University Press. p16-31

[5] Valliani, M., 2017. Reparative Approaches in Medicine and the Different Meanings of “Reparation” for Women with FGM/C in a Migratory Context. [online] Diversityhealthcare.imedpub.com. Available at: <https://diversityhealthcare.imedpub.com/reparative-approaches-in-medicine-and-the-different-meanings-of-reparation-for-women-with-fgmc-in-a-migratory-context.pdf> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[6] Kenyatta, J. and Malinowski, B., 1953. Facing Mount Kenya. London: Secker and Warburg.

[7] Père Daigre and Tastevin, C., n.d. Les Bandas de l'Oubangui-Chari (Afrique Equatoriale Française). [online] JSTOR. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40446310> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[8] de Villeneuve, A., 1937. Étude sur une coutume Somalie : les femmes cousues. Journal de la Société des Africanistes, 7(1), pp.15-32.

[9] Vasquez, J. and Prudhomme, C., 2007. Une cartographie missionnaire. [S.l.]: [s.n.].

[10] Villani, M., 2014. Médecine, sexualité et excision. Sociologie de la réparation clitoridienne chez des femmes issues des migrations d’Afrique sub-saharienn. [online] Tel.archives-ouvertes.fr. Available at: <https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02150806/document> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[11] Ruger, J., 2014. International institutional legitimacy and the World Health Organization. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(8), pp.697-700.

[12] Kapilashrami, A 2022,Understanding Global Health Architecture, Queen Mary University, London.

[13] Refugees, U., 2002. Refworld | Sudan: The Sudanese Women's Union (SWU) including activities, roles, organization and problems faced in Sudan. [online] Refworld. Available at: <https://www.refworld.org/docid/3df4bea84.html> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[14] Openknowledge.worldbank.org. 2021. Compendium of International and National Legal Frameworks on Female Genital Mutilation. [online] Available at: <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/35112/Compendium-of-International-and-National-Legal-Frameworks-on-Female-Genital-Mutilation-Fifth-Edition.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[15] Globalforumljd.com. 2022. Partners View | Global Forum on Law, Justice and Development. [online] Available at: <https://globalforumljd.com/new/partners-view> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[16] Ofpra.gouv.fr. 2022. Demander l'asile en cas de mutilation sexuelle féminine | OFPRA. [online] Available at: <https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/fr/asile/la-procedure-de-demande-d-asile-et> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[17] Vie publique.fr. 2022. Comment la France se situe-t-elle entre le modèle bismarckien et le modèle beveridgien d'État providence ?. [online] Available at: <https://www.vie-publique.fr/parole-dexpert/24117-france-quel-modele-detat-providence-bismarckien-ou-beverigien> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

[18] Altman, D., 2004. Sexuality and Globalisation. [online] Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4066674> [Accessed 17 February 2022].

Critical appraisal of the Cost-Effectiveness of Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention in a South African Setting

Critical analysis of the neo classical theory in sexual and reproductive health, is Capitalism good for your health?

In this paper, we will try to go through the main concepts linked to the neo classical theory. The essay will be in 4 parts:

First, we will discuss the concept of demand of health and health seeking behavior using the example of illegal abortion.

Second, we will try to define 3 of the main key market structures using several examples.

Since pareto efficiency isn’t possible in the market of health, market failure takes place through several mechanisms, we will try to study in the third part, one of the market failures through the example of the TCP .

In the fourth part, we will discuss the impact of capitalism on health.

Neo classical theory in health: the case of Abortion in Eastern Mediterranean Region:

Statistically, one in three women will need to have an abortion during her life [1]. Abortion remains highly restricted in EMR , except in Tunisia. Restrictions are based on conservative and religious arguments. Yet, abortions are still widely performed. According to the WHO, in 2003, 2,800,000 unsafe abortions took place in the EMR [2] leading to 12% of all maternal deaths in the region [3].

There seem to be no official data about demand in this context, but depending on the SES, there are options like abortion in unsafe environments or medically assisted abortion performed in private clinics [4] while women with higher SES can afford safe abortion abroad. Women lake agency and are mainly directed in their choices by their income.

The regulatory rigidities make demand and supply of abortion services part of the black market: there are no controls of the quality of the service nor of the price : women have to pay huge amounts of money to access abortion creating a very unequal access to abortion services and to endorse a coast premium due to the risks involved either due to health impact or to possible legal impact. These restrictive laws also discourage women from having complement of abortion service, since they don’t seek post-abortion care [4]

“Better health outcomes for women are a political issue and involve a collective struggle against entrenched male power” [5]. There is a need to legalize abortion and to regulate the market of abortion service provision.

Examples of Key market structures:

Perfect Competition:

Perfect competition is a gold standard that is unattainable since it’s based on assumptions that are quite difficult to assemble in health market. There is usually a limited number of sellers in the market due to patents or licenses, the latter restrict the freedom of entry into the market. Sometimes products can have similar effects, but they aren’t perfectly homogeneous. Finally, buyers (patients) unless being themselves health professionals do not have perfect knowledge about products provided.

On the other hand, depending on the situation, underground market could be more prone to have perfect competition in health market. In contexts where abortion is illegal, providers can theoretically enter or exit the black market if they bare the risks and can provide either medical or surgical abortions. Buyers aren’t agent but they can make a choice depending on their income. Knowledge about the services is disseminated unofficially through trust networks [6]. It is a largely unregulated market rising concerns about the quality and safety of the abortion services.

Oligopoly:

Oligopoly is a type of imperfect competition that involves few firms, with restricted entry for new firms. Oligopolistic firms have control over price.

Oocytes freezing is turning into an increasingly important demand due to demographic and societal changes. Yet, this demand isn’t satisfied due to restrictive laws.

These restrictions made firms set up in countries where the law allows oocyte freezing.

If we take the example of IVI clinic[7]which operates in London, Dubai, Portugal and Spain and which offers its services around the world, we can talk about a collusive oligopoly where a low number of firms operate in many countries with a restricted entry into the market because of they developed a specialized production and marketing skills. Those firms around the world are sharing information about production methods with each other.

This Oligopoly might disappear if regulations change and they are starting to, since in France, the change in the bioethics law that occurred in august 2021, gives the right to French women to freeze their oocytes without medical reason [8].

Monopoly:

Abortion services in an illegal context can also be a monopoly since risks taking in the black market, can be a barrier to entry.

Monopoly market is a single seller market with diverse barriers to enter the market for other producers. Monopoly is the art of eliminating competition. Monopolistic firms aren’t price takers but rather price makers.

Monopoly creates a dependency situation that can become critic.

The most recent example took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a huge rise in the demand of many medical tools. Monopolistic firms controlling the market through patents and through signing bilateral commercial licensing and purchase agreements couldn't ensure the sufficient supply which undermined access for many developing countries.

This led to a proposal by South Africa and India to temporarily waive monopolies on COVID-19 medical tools during the pandemic [9].

The discussions didn’t have the hoped outcome since EU leaders maintained their support to the existing TRIPS [10]; while the US allegedly supported a vaccines waiver which discussions upon are still stuck while some countries are facing a 5thCOVID wave [11].

Rich countries are backing pharmaceutical corporations and opposing such initiatives in very critical situation. There is a need to decolonize the market.

Market failure, the example of the Tunisian Central Pharmacy:

Market Power is one of the most important market failures that happens when there is a monopoly.

The drug market in Tunisia is composed by 48% of imported goods and 52% of goods provided locally. The TCP [11]is a public institution that is the exclusive supplier of public and Para public health establishments, for imported drugs (76%) [12] but also for drugs produced locally (24%) [12]. It also ensures the monopoly of the importation and supply of medicines and all other medical products in the country [12].

It aims to maintain the regularity of the supply and the quality of the goods as well as their distribution which allows it to rule out any competition [13].

Barriers to entry are legal and offer exceptional custom conditions allowing the clearance of products transiting to the TCP [14].

The TCP is experiencing the same debt as the Tunisian health sector leading to shortages in drugs [15] and the deterioration of its relationships with its suppliers [12].

In this context and despite the continuous increase in its business volume, the TCP has seen all of its margins decline over the last few years in particular due to exchange losses [12]. This had an impact on the availability of drugs in general, including vital drugs and oral contraceptive at some point.

The state intervention shouldn’t jeopardize the sustainability of the healthcare provision. Though being a very good prototype that ensures safety in medical supply, the TCP is lacking a proper budget that would give it the means of its aspirations.

Is Capitalism bad for your health?

Capitalism is the economic system that derive from the market theory. It is based on 6 main pillars which are private property, self-interest, competition, market mechanisms defining prices of goods, agent rational consumers and a limited government intervention [16].

For many reasons, markets fail to establish perfect competition and the actual market fundamentalism divorces economics from social capital [17].

Under capitalism, humanity moved from a market economy to a market society which changed and corroded society mechanisms [17], undermining the satisfaction of the human psychological needs [18].

Indeed, capitalist political and social structures impose a production mode that alienate workers and consumers [18]. Producers objectify workers and clients [19] which disable the “healthy and happy development” of the individuals in capitalist societies [20].

For workers, due to routinization, job stratification and loss of meaning, work becomes detrimental to mental health, leading to burnout [19].

Studies show that workers in capitalistic societies are experiencing normalized work-related degradation of mental health [18].

The WHO reports that “stress at work is associated with a 50% excess risk of coronary heart disease, and there is consistent evidence that high job demand, low control, and effort-reward imbalance are risk factors for mental and physical health problems”.

For consumers, the spread of subjective neutral values based on market price flatted values and lead to underinvestment in what matters for the wellbeing. Competition and individualism combined deteriorated the social capital and lead to consumerism as an attempt to express social position.

Consumers experience loneliness, alcohol and drug abuse, physical and mental health issues, because capitalism divorces humans from their own nature [18].

In addition, oppression and discrimination aiming to ensure optimal markets, lead to racism, sexism, violence against women [21]and economic inequality [18].

Capitalism is based on principals that aren’t adapted to the irrational and impatient humans. As Thaler & Sunstein, point out in their book Nudge, capitalism would be perfect for “mythical Econs”. Meanwhile, it is impacting negatively the health and the environment through overproduction and overconsumption.

New philosophical approaches to economy are getting developed and might be an alternative for capitalism. The economist Gunter Pauli proposes an economic model namely the Blue economy which promotes a more rational use of resources and production systems.

References:

[1] Mazuy,M., Toulemon, L. and Baril, E., 2015. Un recours moindre à l’IVG, mais plus souvent répété. Population &Sociétés, N 518 (1), p.1.

[2] Eastern Mediterranean Region: EMR include: Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates & Yemen.

[3] Unsafe abortion Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003 [Internet]. Apps.who.int. 2003 [cited 26 November 2021]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43798/9789241596121_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[4] Saja M. Women’s Right to Abortion in Lebanon A Position Paper by Nasawiya [Internet]. Theaproject.org. 2021 [cited 26 November 2021]. Available from: https://theaproject.org/sites/default/files/Newest-Abortion-Position-Paper.pdf

[5] Kevin Deane & Joyce Wamoyi (2015) Revisiting the economics of transactional sex: evidence from Tanzania, Review of African Political Economy, 42:145, 437-454, DOI: 10.1080/03056244.2015.1064816

[6] Rubai K. View of Trust without Confidence: Moving Medicine with Dirty Hands | Cultural Anthropology [Internet]. Journal.culanth.org. 2021 [cited 28 November 2021]. Available from: https://journal.culanth.org/index.php/ca/article/view/4711/530

[7] http://hello.apricity.life/ivf/ [Internet]. Hello.apricity.life. 2021 [cited 28 November 2021]. Available from: https://hello.apricity.life/ivf/?utm_site_source_name=website&utm_source=google&utm_medium=paid%20social&utm_campaign=WINNERS-GENERAL-MAX-CONV&utm_term=EM&utm_content=ivf%20london%20clinic&utm_creative=526890964761&gclid=Cj0KCQiA7oyNBhDiARIsADtGRZbXMavfKgtim_WAft0MwPt6HppSGoyJThW3dxmjHCFYVGjVJV_XNF8aAvePEALw_wcB

[8] Congélation des ovocytes en France : 5 questions sur les nouvelles règles [Internet]. LCI. 2021 [cited 28 November 2021]. Available from: https://www.lci.fr/societe/video-toutes-les-francaises-peuvent-desormais-faire-congeler-leurs-ovocytes-voici-les-regles-2198079.html

[9] MSF to wealthy countries: Don’t block and ruin the potential of a landmark waiver on monopolies during the pandemic [Internet]. Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign. 2021 [cited 28 November 2021]. Available from: https://msfaccess.org/msf-wealthy-countries-dont-block-and-ruin-potential-landmark-waiver-monopolies-during-pandemic

[10] World Trade Organization TRIPS waiver to tackle coronavirus - Think Tank [Internet]. Europarl.europa.eu. 2021 [cited 28 November 2021]. Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_ATA%282021%29690649

[11] Beattie A. Talks to waive patents on Covid vaccines are ‘stuck’, WTO head warns [Internet]. Ft.com. 2021 [cited 28 November 2021]. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/b9a66140-f031-4ed6-9048-f6029832c511

[11] Development Aid [Internet]. DevelopmentAid. 2021 [cited 6 December 2021]. Available from: https://www.developmentaid.org/#!/organizations/view/237179/central-pharmacy-of-tunisia-pharmacie-centrale-de-tunisie

[12] La pharmacie centrale de Tunisie Mission [Internet]. Phct.com.tn. 2021 [cited 6 December 2021]. Available from: http://www.phct.com.tn/index.php/apropos/mission

[13] La Pharmacie Centrale de Tunisie notée ''CCC'' avec perspective stable par PBR Rating [Internet]. ilboursa.com. 2019 [cited 6 December 2021]. Available from: https://www.ilboursa.com/marches/la-pharmacie-centrale-de-tunisie-notee--ccc--avec-perspective-stable-par-pbr-rating_19018

[14]Souissi Jaziri, Camelia, & Moulahi, L. (2013). Role of the tunisian central pharmacy in the import of radio-pharmaceutical products. International Conference on Radioisotopes Production and Utilisation : Radioisotopes and health, Book of abstracts, Tunisia (TN), 16-17 May, 2013, (p. v). Tunisia: National Center for Nuclear Sciences and Technologies.

[15] Tunisia allocates $190m to reduce Central Pharmacy deficit [Internet]. Middle East Monitor. 2018 [cited 6 December 2021]. Available from: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180629-tunisia-allocates-190-million-to-reduce-central-pharmacy-deficit/

[16] Sarwat J, Mahmud A. What Is Capitalism? Free markets may not be perfect but they are probably the best way to organize an economy [Internet]. FINANCE & DEVELOPMENT. 2021 [cited 8 December 2021]. Available from: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/2_capitalism.htm

[17] The Reith Lectures - Mark Carney - How We Get What We Value - From Moral to Market Sentiments - BBC Sounds [Internet]. bbc. 2021 [cited 8 December 2021]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000py8t

[18] Matthews D. Monthly Review | Capitalism and Mental Health [Internet]. Monthly Review. 2019 [cited 8 December 2021]. Available from: https://monthlyreview.org/2019/01/01/capitalism-and-mental-health/

[19] Karger H. Burnout as Alienation [Internet]. 2021 [cited 8 December 2021]. Available from: http://www.jstor.com/stable/30011472 (Links to an external site.)

[20] Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy, Monopoly Capital (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966), 285.

[21]Federici S. Crise du capitalisme et violences sexistes. Entretien avec Silvia Federici – CONTRETEMPS [Internet]. Contretemps.eu. 2021 [cited 8 December 2021]. Available from: https://www.contretemps.eu/crise-capitalisme-et-chasse-aux-sorcieres-entretien-avec-silvia-federici/

Access to safe abortion for migrant women in France

Women's health depends on the guarantee of their sexual and reproductive rights. Historically, the legislation around these rights has been and remains a major issue for the emancipation of women around the world.

In France, contraception and voluntary termination of pregnancy (abortion) are legal and theoretically available to any woman wishing to benefit from them, as part of a public health policy aimed at equal access to primary care. Statistically, one in three (1) women will need to have an abortion during her life.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, the French legislator has adapted the legal framework authorizing general practitioners to perform abortions in town offices1, in family planning centers and health centers2. The law thus adapts to the practices and needs of patients, approaching abortion as an act of first necessity and a real public health issue.

Women’ migration is becoming an important component of international migration. The UN report on international migration (2) shows that nearly half of the 272 million international migrants worldwide in 2019, were women.

In France, percentage of female among all migrants’ range between 50 to 52%

(2) There is a great variety of migrant women with different socio-economic status, they can be documented or undocumented and might have different linguistic capabilities and ethnic backgrounds. Nevertheless, studies show that female migrants have similar characteristics since they face intersecting vulnerabilities of gender, ethnicity and social class (3) and might experience violence (4).

Unsuccessful access to safe abortion services is a reality even in countries with very advanced policies (5). Migrant women seem to be more vulnerable to unwanted pregnancies (6) and often face more challenges to access sexual and reproductive health services than the local population (7).

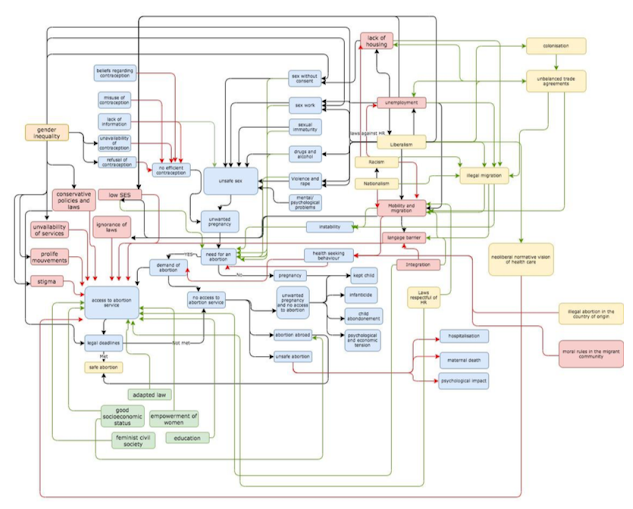

This article will focus on social determinants to access safe abortion services in low-skilled and low-wage economic female migrants in France through the Abortion system Map. The main objective of this article is to explore the various social determinants of vulnerabilities that may hinder access to the medical abortion course for this population through a critical analysis of the Abortion system map.

Access to abortion system map:

Unintended Pregnancy is a consequence of interplay between determinants related to individual physiology, sexual behavior and contraception. This individual behavior is set in a framework designed by many interconnected factors.

Access to abortion system map is made up of a large number of determinants.

Variables are represented by boxes: social determinant that are barriers are in red and the enablers are in green.

Interactions are represented by arrows: positive feedback is represented in green and negative feedback is represented in red.

The central loop is the physiological loop and it is represented in blue. This loop tackles the SDH3 at the individual and familial level.

The green enablers and red barriers tackle the SDH at the social level. The yellow and white boxes tackle more distal Macroenvironmental SDH. Critical analysis of the access to abortion system map:

The access to abortion system map improves the insight into the underlying structure of this complex health issue but doesn’t show the level of influence between variables. Indeed, migration seems to intensify barriers.

This system map is also made up of a number of determinants, some are measurable while others are difficult to quantify.

At the individual level, it presents the contraception as a women’s issue: in this framework men aren’t involved neither in contraception, unsafe sex nor in unwanted pregnancy. The risk is to exclude men from sexual and reproductive health programs’ planning.

Literature shows that vulnerable migrant women in European countries, have less individual agency (8): tend to have limited use and access to contraception and abortion and might look for unsafe abortion procedures (9,10). They seem to be relying on less effective methods of contraception so unintended pregnancy and abortion are common. (11)

One can also argue that these patients might also have a different health services seeking behaviors since in several countries of origin, abortion is prohibited by law and sometimes, depending on the contexts, there may be traumatic or post

-traumatic conditions (12).

But a study shows that this Sick-role behavior (13) is more influenced by cultural issues than the legal interdiction of this practice (14).

At the social level, Mobility and migration are crucial determinants that can affect vulnerability to unintended pregnancies flowing similar mechanisms as in HIV transmission (15). Some authors also link this to the change of the socioeconomic and cultural contexts before and after migration (16).

Social Determinants of Health

At the global level, this framework takes into consideration the politicized dimension of sexual health as a form of biopower: through the strict definition of the duration of pregnancy that gives the right to abort, the government controls women's bodies. During COVID crisis, restrictive measures and reduced freedom of movement obstructed access to safe abortion. Many patients missed the legal deadline. Lately, a law proposition has been discussed and validated to extend the legal period from 12 to 14 weeks for having recourse to abortion (16).

Policies implications and recommendations:

Safe abortion is a universal complex health issue that needs a multidimensional response. The priority is to focus on proximal barriers in order to have quick improvements.

The social and economic forces that constrain the agency of vulnerable migrant women need to be addressed first through actions aiming proximal SDH like language barriers, dissemination of information through channels adapted to each population, better employment conditions. Then distal SDH need to be addressed through flexible policies as in the Netherlands, where abortions are performed until approximately 24 weeks of pregnancy.

In conclusion, a feminist approach is needed within mobility studies in order to produce data about the “creation of new geographies of belonging and exclusion” (17) which has a great impact on health in migrant women.

“Never forget that a crisis will suffice for women’s rights to be threatened. These rights are never granted. You need to remain careful, your entire life”. (Simone Veil)

Notes:

1 law n ° 2001-588 of July 4, 2001

2 law n ° 2007 -1786 of December 19, 2007

References:

1. Mazuy, M., Toulemon, L. and Baril, É., 2015. Un recours moindre à l’IVG, mais

plus souvent répété. Population & Sociétés, N° 518(1), p.1.

2. United Nations department of economic and social affairs Population Division. 2019. International migrant stock 2019. [online] Available at:

<https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates 2/estimates19.asp.> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

3. Llacer, A., Zunzunegui, M., del Amo, J., Mazarrasa, L. and Bolumar, F., 2007. The contribution of a gender perspective to the understanding of migrants' health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, [online] 61(Supplement 2), pp.ii4-ii10. Available at:<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2465778/> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

4. ReliefWeb. 2021. UNFPA State of World Population 2006: A Passage to Hope - Women and International Migration - World. [online] Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/report/world/unfpa-state-world-population-2006-passage- hope-women-and-international-migration> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

5. Klein, J. and von dem Knesebeck, O., 2018. Inequalities in health care utilization among migrants and non-migrants in Germany: a systematic review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1).

6. Rokicki, S., Montana, L. and Fink, G., 2021. Impact of Migration on Fertility and Abortion: Evidence from the Household and Welfare Study of Accra. [online] Available at:<https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/slawarokicki/files/rokicki_migrationfertility_wp_0.pdf> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

7. Foundation, T., 2021. What the lack of access to safe abortion means for migrant women. [online] news.trust.org. Available at:

<https://news.trust.org/item/20190927142655-3gkuh/> [Accessed 6 June 2021].

8. Clark University, and International Center for Research on Women, 2021. the AIDS Response: Building AIDS Resilient Communities, International Development, Community and Environment. Aids2031. [online] Washington: Social Drivers Working Group (2010). Available at:

<https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rj a&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwi6_qGljYnxAhWDyIUKHTDPBOEQFjABegQIBBAD&url

=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.comminit.com%2Fla%2Fcontent%2Frevolutionizing- aids-response-building-aids-resilient-communities-aids-2031- internationa&usg=AOvVaw0hDDRQlK5bPN97wtODmc4E> [Accessed 1 June 2021].

9. PICUM. 2016. The Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights of Undocumented Migrants: Narrowing the Gap between their Rights and the Reality in the EU.. [online] Available at: <http://picum.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Sexual-and- Reproductive-Health-Rights_EN.pdf> [Accessed 4 June 2021].

10. Emtell Iwarsson K, Larsson E, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Essén B, Klingberg-Allvin

M. Contraceptive use among migrant, second-generation migrant and non- migrant women seeking abortion care: a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted in Sweden. 2020.

11. Zong Z, Sun X, Mao J, Shu X, Hearst N. Contraception and abortion among migrant women in Changzhou, China. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2020;26(1):36-41.

12. Vilain A. Les femmes ayant recours à l'IVG : diversité des profils des femmes et des modalités de prise en charge. Revue française des affaires sociales. 2011;1(1):116.

13. 4. Kasl S, Cobb S. Health Behavior, Illness Behavior, and Sick-Role Behavior. Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. 1966;12(4):531-541.

14. Pilecco F, Guillaume A, Ravalihasy A, Desgrées du Loû A. Induced Abortion and Migration to Metropolitan Paris by Sub-Saharan African Women: The Role of Intendedness of Pregnancy. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2020;22(4):682-690.

15. O'Laughlin B. Trapped in the prison of the proximate: structural HIV/AIDS prevention in southern Africa. Review of African Political Economy. 2015;42(145):342-361.

16. Quatre questions sur la proposition de loi visant à renforcer le droit à l'IVG en France [Internet]. Les Echos. 2021 [cited 6 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.lesechos.fr/politique-societe/societe/quatre-questions-sur-la- proposition-de-loi-visant-a-renforcer-le-droit-a-livg-en-france-1254110

17. . Side K. A geopolitics of migrant women, mobility and abortion access in the Republic of Ireland [Internet]. Academia.edu. 2016 [cited 6 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/30578728/A_Geopolitics_of_Migrant_Women_Mobilit y_and_Abortion_Access_in_the_Republic_of_Ireland

La Santé Sexuelle est au centre de la Santé à tout âge

(Présentation à l’occasion de l’Université Populaire)

La sexualité est plus fragile chez les personnes âgées , puisqu’elles subissent des critiques de leur entourage et peuvent avoir une mauvaise image d'elles-mêmes et douter de leur capacité à séduire.

En effet, il s’agit d’un tabou qui pèse lourdement sur les séniors, dans la majorité les sociétés modernes : les parents vivent la stigmatisation des enfants qui portent un regard moralisateur et castrateur sur leurs ainés, comme le dit si bien Sardou dans sa chanson la fille aux yeux clairs : « Je n’imaginais pas les cheveux de ma mère Autrement que gris-blanc… Je n’aurais jamais cru que ma mère ait su faire un enfant... Je n’aurais jamais cru que ma mère… Ait pu faire l’amour. »

Pourtant, plusieurs études montrent que les plus de 80 ans ont toujours des fantasmes sexuels et un désir intact.

Contrairement aux idées reçues sur le vieillissement, ce dernier n’est pas l’équivalent d’une détérioration ou d’un déficit puisque l’amélioration des conditions de vie et l’accès aux services de santé ont permis une bonne espérance de vie en bonne santé après la retraite dans plusieurs pays.

Le vieillissement est un processus normal qui implique la modification de quelques performances sans pour autant que les maladies et surtout les troubles de la mémoire ne soient une conséquence « NORMALE » du vieillissement.

Malgré les pressions sociales, la vie sexuelle, les envies sexuelles et la sexualité ne disparaissent pas avec l’âge : les humains continuent à avoir une vie sexuelle diverse et variée avec l’âge, peuvent entretenir des relations établies ou en bâtir de nouvelles.